Wikidworld (#139) / How Clothes Make the Law: John Fetterman's Hoodie and Catholic Natural Law

Fetterman’s charm is that he does not slot crisply into the fixed social scaffolding of order, status, hierarchy, degree, boundary, and convention that conservatives and traditionalists so value.

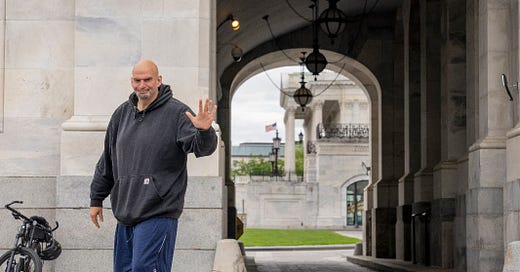

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s decision to relax the dress code in Senate chambers has elicited outrage and dismay from Republicans. Much of this scorn has targeted Pennsylvania’s hulking, iconoclastic first-term senator, John Fetterman, who eschews the traditional suit-and-tie, preferring to stalk the Senate chambers in baggy shorts and a hoodie.

A letter to Schumer signed by 46 Republican senators stated, “Allowing casual clothing on the Senate floor disrespects the institution we serve and the American families we represent.” Ron DeSantis and Marjorie Taylor Greene denounced Fetterman’s fashion choices as “disgraceful” and “disrespectful.” This self-righteous Republican meltdown illuminates huge swaths of our political landscape.

Clothes have always fascinated as markers of status, identity, and personality. I wrote about clothing at some length in the second season of Wikidworld, with a specific focus on the liturgical significance of the clerical costumery of the Catholic Church and the black robes of Supreme Court justices. The point of these vestments, amidst all of the ceremonial puffery of the Church and Court, is that we bend the knee to the trappings, not to the person.

Consider the idioms, to take the cloth or don the robe. The identity and presence of a Catholic bishop or a Supreme Court justice is like a perfume. It is 80 percent atmospherics. It is a dream. We want to believe these actors fully inhabit their roles in dramas of salvation and justice. Their vestments tell us they must. And so we’re grievously disappointed when these luminaries fall to earth and reveal themselves to be largely imperfect and fully human.

Fetterman’s charm is that he does not slot crisply into the fixed social scaffolding of order, status, hierarchy, degree, boundary, and convention that conservatives and traditionalists so value, which they imagine is all that keeps chaos at bay. Fetterman represents a disconcerting fluidity and disorder in the halls of power that threatens to dissolve the great chain of being.

These incongruities greatly discomfit traditionalists. Far moreso, it seems, than do the gaucheries and bombast of Donald Trump — a vastly more significant and unseemly agent of chaos, whom we never see outside a golf course without a suit and tie.

But Fetterman also invite comparisons with the two bella figuras of the Catholic conservative establishment — Federalist Society impresario Leonard Leo and Princeton professor Robby George — for whom the stitch and fabric of their vestments are the warp and woof of their natural law values and their counter-Reformation political commitments.

Jeffrey Toobin has famously described Leo’s “tailored suits, often with contrasting waistcoats, and a double-length gold fob attached to a 1935 train conductor’s pocket watch. (‘The most accurate watch in the United States until the fifties,’ he said.)”

As for George — who may well sleep in a three-piece suit — one evening he’s the honored dinner party guest of pathologically ambitious right-wing ingenue, Solveig Gold; the next morning, he’s leading an advanced graduate student seminar on the moral foundations of the law; and that evening finds him drafting a breathtakingly reactionary manifesto such as the Manhattan Declaration. He’s the Thomas More of Princeton University.

I’m not necessarily making a judgment here. Most of us wear different clothes at different times and for different occasions because we play different roles in our lives. When wearing shorts and sandals, a suit and tie, or pajamas (or when simply wearing nothing at all), we adopt varying personas that are to some degree roles. We all play act on a daily basis.

The costume we adopt for each part we perform, in each drama of our lives, is not a superfluity, but an emergent dimension of our self. We fake it until we make it. We become what we wear. Kleider machen den leute.

What therefore is intriguing about Fetterman, Leo, and George is not how their fashion choices distinguish them — partly because these are not really choices at all — but what the reductionist unidimensionality of their attire discloses about their artlessness. They each wear one thing because fundamentally they each are one thing.

John Fetterman’s informality betrays not merely a democratic sensibility, but a personal vulnerability. As has been widely reported, he was hospitalized for serious depression shortly after taking office. This malady had been preceded by a serious stroke while campaigning for office that nearly killed him.

A small-town politician for the bulk of his adult life, Fetterman — despite his size — is small in other ways. Enormously empathetic, he lives to serve others partly because he is himself so humble and self-effacing. The law as he visualizes it is about reshaping the given order to provide security and opportunity to those without.

By contrast, Leonard Leo and Robby George live large, their three-piece suits evidence of both their patrician self-regard and their unyielding focus on cultivating those in positions of enormous wealth and power. Their stated life’s work has been to leverage the positive law to reinforce — or to establish anew — moral and civilizational conceptions of order derived from the natural law.

Leo and George will reference the soul, but their true commitment is to the control of bodies, which they associate with sinful and concupiscent behavior. Where Fetterman sees suffering, Leo and George witness evil. Where Fetterman associates the law with justice, Leo and George pair law with order — or, more precisely, with the battle against disorder.

John Fetterman’s stubborn insistence on dressing down on the Senate floor obviously communicates something very different than the commitment to dressing up of Leo and George. Fetterman is subsuming himself within his constituency — letting them know that he is one of them, that he will never put on airs that would elevate him above them.

Leonard Leo and Robby George are not politicians. They do not need to placate or please or pander. But they are nonetheless feral political creatures. Their clothing is inseparable from their mission, which is to make Catholic natural law the foundation of our political and legal institutions. Not merely the plinth of a statue, but its animating essence. For Leo and George, it is the law that makes the man. Gesetz machen den leute.

Which by the logic of transitivity allows us to conclude that the clothes make the law. Kleider machen den gesetz.