Wikidworld (#130) / Inquisition: The Body as Text

It’s not a stretch to conceive of the inscribed bodies of the torture chamber and auto-da-fe as a counter-library of pain designed to rival those libraries assembled from the moveable type press.

I need to touch briefly on the Spanish Inquisition because it represents the fulfillment and perfection of the idea of Inquisition itself. The consequences are enormous for the subsequent history of the West.

As with the medieval Inquisition, the stated goal of the Spanish Inquisition — which commenced in the latter portion of the 15th century — was to combat internal enemies within the Christian Church, to conduct an internal Crusade. Of course, this theme that a people are threatened with enemies within — that those “closer to you than your shirt” may be the ones you can least trust — is a common refrain in the history of any politics associated with moral and doctrinal purity.

We witness this obsession in the history of various 20th-century Communist regimes and, notably, also in the history of various 20th-century Catholic-sponsored and supported anti-Communist crusades in the United States. We witness this obsession today in right-wing rhetoric concerning illegal aliens and “woke communists.”

But the first appearance of this collective paranoia occurred during the medieval and Spanish Inquisitions, when inquisitors turned people who had lived together across many generations against each other. We might see this efforts to “scale mistrust” as a meaningful inversion of the proposition advanced by Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens concerning the significance for the Homo sapiens of the capacity to scale trust, communication, and cooperation.

The centrality of the “anonymous informant” to the script of the inquisitorial trial thrived and was nurtured in a climate of fear, bringing out the worst in one’s neighbors, exploiting the vulnerability of those seeking to protect their own families, the opportunism of those with grudges or scores to settle with neighbors, and those simply wishing to profit from betrayal.

During the Papal and Spanish Inquisitions, the compulsion to locate and root out enemies hiding in plain sight played out through legal methods developed specifically to extract confessions and other forms of intelligence pertaining to the subversions and perversions of wayward Christians. Indeed, the nature of the Inquisition as a legal institution was that its jurisdiction only extended to Christians. It only applied to those in a position to undermine the Church from within by proclaiming or practicing heretical views that challenged the doctrinal and institutional core of the Church.

Definitionally, practitioners of Judaism and Islam therefore fell outside the ambit of the Inquisitorial apparatus. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spain enforced the conversion of Jewish (Converso) and Muslim (Morisco) inhabitants (despite the Catholic Church’s insistence that conversion must always be voluntary). Those who refused to convert were expelled from Spain, the first significant expulsion of unconverted Jews occuring in 1492. Islamic rule in Spain also ended in 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the last Sultan from the Alhambra in Granada and brought all of Spain under unified Catholic rule.

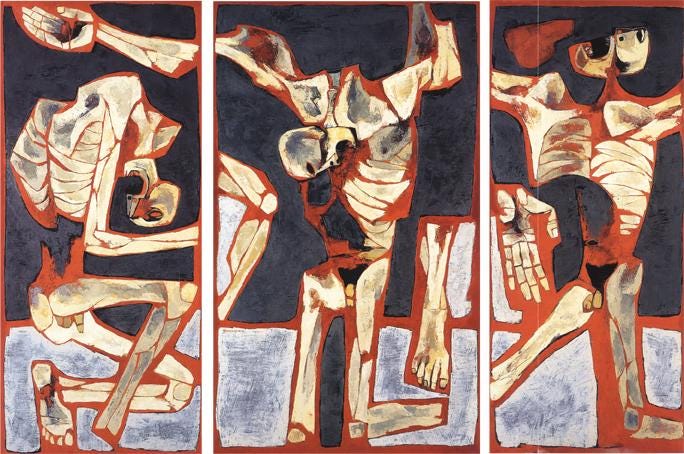

Revealed religion’s reliance on written texts to access eternal or fundamental truths obscures the extent to which ritualized ceremonial and judicial practices created a liturgy of their own that inscribed and textualized the material world. Iberian inquisitions of Jewish conversos and Islamic moriscos during the late Middle Ages “published” the bodies of the accused as texts, inscribed by “genre-like” rituals of forced conversion, expulsion, torture, and confession (illuminated by the fire of the auto-da-fe).

Consider the book censorship initiatives practiced by the Spanish and Roman Inquisitions in response to the printing revolutions of the 16th and 17th centuries, which were believed the hasten the spread of heretical ideas. The Council of Trent in the 1540s — which launched the Counter-Reformation — enacted strict publishing rules requiring Catholic books to get ecclesiastical approval before printing.

In the 1550s and 1560s, the Church published the Index Librorum Prohibitorum — an index of banned books Catholics were forbidden to read. At this times, local inquisitions also jumped on the censorship bandwagon. Printing permits were revoked if printers violated bans.

It’s therefore not a stretch (pun intended) to conceive of the inscribed bodies of the torture chamber and auto-da-fe as a counter-library of pain, informing the consciousness of the Western mind in a manner designed to rival those texts published using the newly invented moveable type press.

The idea of “the West” emerged from the Christian experience of engagement with everything that was not-Church, beginning with Charles Martel’s victory over the invading Islamic army in the 7th century Battle of Tours. This triumph cemented the notion that identity may be less about who you are than who you are not.

Even today, this decisive military moment for the subsequent history of Christianity and for “Western Civilization” — for who “we” are today — resonates enormously with religious traditionalists and “post-liberal” nationalist conservatives. Fourteen centuries have passed since the Battle of Tours. Christian reactionaries continue to view Islam as an existential enemy committed to infiltrating and destroying from within the West.

Despite the universal aspirations of the Thomist natural law synthesis that emerged some six centuries later, the medieval Church between the 12th and 16th centuries spawned vast "subduction zones" on and beyond the Catholic borders of Europe, a source of enduring tensions in the subsequent history of the West. Juxtaposition of the core values, beliefs, and practices of the Church with those of groups and communities it shunted to the margins, usefully redirects our attention from the core to the periphery of the most powerful medieval institutions.

In this period, natural law’s ethical precepts and commitments guided or influence the Catholic Church in the application of canon law to root out heresy, dispel magic, and deport Abrahamic rivals. But philosophies of natural law were helpless to even comprehend, much less counter, the juridically conflagratory underpinnings of Crusades and Inquisitions incepted by Church canon law.

As a consequence of the lingering harms inflicted upon the Iberian Peninsula by these Inquisitional spasms (what we would today call ethnic cleansing), Iberia became a crucible, a compression point for tensions between Christianity and Islam, hardening and brutalizing relations between social classes on the peninsula, which of course culminated during the 20th century in the civil war in Spain (in this respect, Iberia itself becoming a text).