Wikidworld (#108) / The Political Theology of the Middle Ages

Andrew Willard Jones wants to persuade you that the distinctions and separations between Church and State that we take for granted would have been meaningless to people during the Middle Ages.

I’d like to take the next two newsletters to write about Andrew Willard Jones, a medieval historian and one-man publishing juggernaut over whom Catholic conservatives have been swooning since the publication in 2017 of his first major book, entitled Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX.

In 2021, Jones published an even more ambitious work, a rewriting of the political history of Western Civilization “with a new plot, a plot in which Christianity is true, in which human history is Church history.” The title of this book is The Two Cities: A History of Christian Politics.

I’ll introduce Jones, his ideas, and his influence, in today’s newsletter and follow up by engaging his book on religion and politics in 13th-century France in Friday’s newsletter. Which will be fun, because Andrew Willard Jones — who is both brilliant and preposterous — brings both a lot and a little to the table. Here’s a foretaste.

Christianity is not an aesthetic for well-functioning liberals. The Church is a military operation, a kingdom that seeks to submit all other kingdoms to its rule—giving no quarter. Christ came to bring not peace, but the sword. The Church is made up of zealous warriors.

Andrew Willard Jones is Director of the Catholic Studies Program at Franciscan University of Steubenville and the editor of New Polity Magazine. Jones obtained his undergradate degree from Hillsdale College, which has been much in the news recently because of its leading role in Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s efforts to remake public universities in Florida into citadels of Christian virtue.

Jones also holds a PhD in Medieval History from Saint Louis University, where his research focused on the Church of the High Middle Ages. Methodologically, his work “treats history as a theological discipline and not as a secular archaeology.” In other words, Jones’s historical methods and publications are inseparable from his evangelism on behalf of the Catholic Church and the gospel vocation.

Franciscan University of Steubenville is a private university in Steubenville, Ohio, part of an ecoystem of small Catholic colleges and universities that wields enormous influence in conservative politics, but which has remained largely beyond the purview of mainstream discourse. The student body at Franciscan University is 97 percent Catholic. The university reports having the largest number of students majoring in theology, catechetics, and philosophy of any Catholic university in the United States.

New Polity Magazine is a relatively new publication — also fully based out of Steubenville, Ohio — that “aims to deconstruct the keywords and categories of liberalism and reconstruct them according to the logic of Christianity.” New Polity presents itself as a conservative Christian alternative to the “post-liberal” integralism of the National Conservative movement and to the authoritarian vibe of publications such as Sohrab Ahmari’s Compact.

For my Friday newsletter, I’ll focus specifically on Andrew Willard Jones’s book, Before Church and State, which wants to persuade you that the distinctions and separations between Church and State — and between religion and politics — that we take for granted would have been meaningless to people during the Middle Ages.

Whether this is quite the breathtaking insight that Jones assumes remains to be seen, but the book is nonetheless remarkable for its voracious scholarship and its neo-Scholastic methods. It is perhaps the most intellectually engaging study of the political theology of the Middle Ages since Ernst Kantorowicz’s The King’s Two Bodies, which I’ll write about next week.

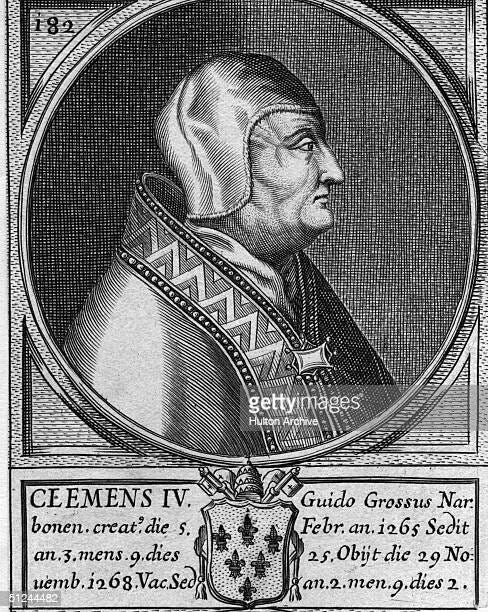

Before Church and State follows the life of Gui Foucois, the son of a prosperous lawyer who was born in the County of Toulouse in southern France in 1190. Also known as Guy le Gros or Guido Grossus (French and Italian for “Guy the Fat”), Gui Foucois fought the Moors in Spain at the age of 19, studied law, aquired influence in Paris as a prominent advocate, acted as secretary to King Louis IX, married, and had two daughters.

Upon the death of his wife, Gui abandoned secular life for the Church. In 1264, then the Cardinal of Sabina, Gui renewed the prohibition of the Talmud promulgated by Pope Gregory IX, who had it publicly burnt in France and in Italy. Gui did not condemn to death at the stake those who harboured copies of the Talmud. However, he ordered that the Jews of Aragon submit their books to Dominican censors for expurgation.

In 1265, Gui was elected Pope, taking for himself the name Clement IV. As Pope, Clement was a patron of both Thomas Aquinas and the Franciscan philosopher and scientist, Roger Bacon.

The relationship between Clement and Aquinas is of particular interest. Let’s listen in on Father Placid Conway’s 1911 Biographical Study of the Angelic Doctor.

Directly Pope Clement IV assumed the tiara in February, 1265, he summoned Thomas to Rome. If love of truth made our saint always. to seek the quiet of retirement, the call of obedience found him ready for further work. He now put forth another argumentative treatise, begun long before in Paris, in which Arabian pantheism yielded before the power of the syllogism; its title is: "On the Unity of the Intellect, against the Averroists".

Averroes, the cultured Arabian physician, while outwardly professing to be a Christian, was an atheist at heart. Christianity he called an impossible religion, Judaism one for children, Mohammedanism one fit for hogs. The basis of his errors was this, that all men have but the one intellect, and consequently but one soul: consequently, there is no personal morality. "Peter is saved: I am one intellect and soul with Peter; so I shall be saved."

From the appearance of Saint Thomas's work, the philosophy of Averroes was consigned to the antiquities of the buried past.

The summons to Rome of Clement IV in 1265 represented a culmination for Aquinas and Natural Law moral philosophy, the end-point of a social and political logic beginning well before his birth with the election to the papacy of Innocent III in 1198.

In the intervening decades, the legal reforms of Emperor Frederick II and France’s King Louis IX — as well as the systematic transformations to the canon law promulgated by Innocent III, Gregory IX, and Innocent IV — had absorbed elements of the Natural Law as the basis for universalizing and rationalizing the moral authority of both church and state. Natural Law provided the glue that sustains Andrew Willard Jones’s arguments for the unity of religious and political authority in the sacramental kingdom of Saint Louis IX.

Truth be told

Revisions need to be made

We never made it to Rome.

There was a war. We moved the Vatican to the top of a mountain very remote town for security reasons.

Our rule was over all kings of Europe.