Okay. This is the last portion of Chapter One. On Richard Feynman. I start with the final paragraph from what I posted yesterday, for purposes of continuity. I hope you enjoy. It’s pretty wild stuff. And now on to Chapter Two!

Grisez's perspective was that Pope Paul VI was not seeking to delegate decision-making authority to the commission but rather wanted to see what arguments could be made for changing the teaching. As Grisez put it: "[The Pope] was perfectly happy to have a lot of people on the commission who thought that change was possible. He wanted to see what kind of case they could make for that view. He was not at all imagining that he could delegate to a committee the power to decide what the Church's teaching is going to be."

That final message – with the emphasis on the inconceivability of imagining the Pope might ever delegate power to a committee to determine the teachings of the Church, on contraception or anything else – obviously reflects a deeply embedded view of Catholic Church authority. A vision that shares much with - and in some measures likely also contributes to shaping - the unitary executive theories of the Trump administration, and of conservative legal scholars generally, who likewise understand effective, decisive, meaningful political authority to be like the point of a soft lead pencil, ever bearing down and not subject to revision (except for smudges).

We’ll explore dimensions of the unitary executive theory and its aspects of its lineage in medieval Catholic political and legal theories in subsequent chapters. For now, the striking thing about the Birth Control Commission Minority Report is the extent to which – as with the originalist jurisprudence of the legal conservative movement – it relies on historical precedent to justify itself. Building on the notion that the Church derives its authority and its directives, first from God (“the Supreme Judge”) and second from whatever the Church itself has said and done in the past.

And what the Church as always said is that what we are by nature comes directly from God and must always be honored and sanctified, never contravened. The truth, which is singular and unyielding, therefore must receive expression in Church doctrine that conforms to the laws of nature.

What was true at the beginning remains true now and shall always. Trimming the sails of what counts for truth when the winds shift amounts only to epistemic incoherence. And if epistemic incoherence prevails, on contraception or any other matter, then God’s laws and God’s truths mean nothing, and the Church will fall.

The answer of the Church has always and everywhere been the same, from the beginning up to the present decade. One can find no period of history, no document of the church, no theological school, scarcely one Catholic theologian, who ever denied that contraception was always seriously evil. The teaching of the Church in this matter is absolutely constant.

Let’s call this the state of mind of the medieval Catholic Church. In considering matters of truth, which is to say matters of cosmology, the answer matters far more than the question.

In 1963, however, the spirit of scientific inquiry and the search for truth rested on foundations diametrically opposed to those of the Catholic Church. For scientists of the post-Newtonian era, the questions have always mattered far more than the answers. Scientific truth has always been in motion. Its questions race ahead. The answers catch up when they can.

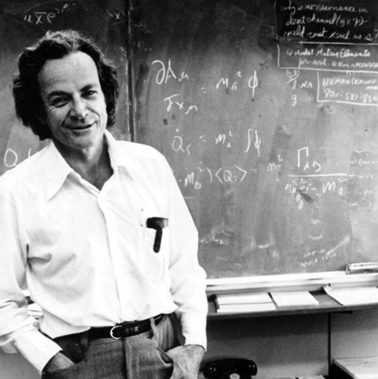

The Exuberance of Richard Feynman

Between 1961 and 1963, renowned Cal Tech theoretical physicist Richard Feynman taught a two-year introductory physics course in a series of lectures now commonly known as the Feynman Lectures on Physics. The lectures were subsequently compiled into a three-volume textbook set which remains even now one of the most influential and widely read physics books in the world. The course was designed as a major revision of Caltech’s physics curriculum, reflecting rapid advances in physics.

In these lectures, we witness several important things. First, in contrast to the existential-unto-death despair of liberal intellectuals such as Perry Miller and the fractious-plotting-spoiling-for-a-fight biliousness of Catholic fundamentalists such as Germain Grisez, what we experience in the Feynman Lectures is the unbridled exuberance of a man raptured by the chaotic order and abundance of the universe.

Second, we’re reminded that quantum physics has its laws, to be sure, but that Feynman - despite possessing hubris in abundance - would be the last to assert they might be pinned down like butterflies in the manner of Catholic Natural Law’s Levitical imperatives.

“We do not yet know all the basic laws,” Feynman tells his students in his first lecture. “There is an expanding frontier of ignorance.” Indeed the cosmology of post-Newtonian science is shaped by looping sensations of awe and wonder and burning curiosity to both sate and loosen their hold upon its practitioners.

What might characterize the differences between the shape-shifting flexibility of post-Newtonian science and the structured formalism of Catholic Natural Law? It is in the difference between an open system and a closed system, a system that is constantly absorbing and processing new information and new energy, knowing only what it doesn’t know, and a system that recursively folds back upon itself, knowing only what it always from the beginning knew. The difference between post-Newtonian science and pre-Newtonian Catholic Natural Law is the difference between something that is alive and something that is dead.

This brief glimpse of Richard Feynman and the post-Newtonian cosmology is a tease. Further along in this book, we’ll return to Richard Feynman as he engages in a conversation with Stephen Hawking and Nassim Nicolas Taleb about heat, motion, entropy, probability, and cosmology. For now, I’ll leave you with Feynman’s invocation to his students, which builds on a few simple propositions.

All is atomic. All is in flux. All is contingent. And yet here we are.

If a piece of steel or a piece of salt, consisting of atoms one next to the other, can have such interesting properties; if water—which is nothing but these little blobs, mile upon mile of the same thing over the earth—can form waves and foam, and make rushing noises and strange patterns as it runs over cement; if all of this, all the life of a stream of water, can be nothing but a pile of atoms, how much more is possible? If instead of arranging the atoms in some definite pattern, again and again repeated, on and on, or even forming little lumps of complexity like the odor of violets, we make an arrangement which is always different from place to place, with different kinds of atoms arranged in many ways, continually changing, not repeating, how much more marvelously is it possible that this thing might behave?

Looks like WSJ and I went down the same rabbit hole. Techbros vs Catholic Fascism.

https://archive.ph/FLRoS

Thanks Tom. All good stuff. And a great list of sources. The CSNY line is so true. I try to conceptualize it in terms of 3-body problem chaos.